|

| Emily Birsan & Evan Hughes in "The Marriage of Figaro" (photo: T. Charles Erickson) |

Mozart's

The Marriage of Figaro

is a challenging undertaking for an opera company to mount, but

Boston Lyric Opera is surely up to the task. Among other hurdles, it

requires no fewer than thirteen singers: two each of bass-baritones,

tenors, and baritones, as well as three mezzo-sopranos and four

sopranos, most of them principal roles. When he composed this opera

buffa in 1786 to a libretto by

Lorenzo da Ponte, though, Mozart would surely never have expected to

see the work performed with as many distractions as the current

production has, including major acoustic problems with the venue at

John Hancock Hall, but more about that later. For the moment, here

is a very brief reminder of all that transpires in this multi-plotted

work.

Figaro (bass-baritone Evan Hughes) and Susanna (soprano

Emily Birsan), servants in an Italian villa in the 1950's (updated by

a couple of centuries), are to be married, but their employer,

sportscar enthusiast (in this production) Count Almaviva (baritone

David Pershall) has been ogling the bride-to-be (droit

d'employeur?). Meanwhile, the housekeeper for Doctor Bartolo

(baritone David Cushing), Marcellina (soprano Michelle Trainor),

wants Figaro for herself (and, to complicate things further, he owes

her money). But this will prove impossible, for relative reasons

(the sort of “reveal” that Gilbert and Sullivan were much later

to make such fun of). Susanna, who is maid to the Countess Almaviva

(soprano Nicole Heaston), conspires with her to outwit the Count by

dressing the Count's teenaged male page, Cherubino (mezzo-soprano

Emily Fons) as a girl. Things get a bit mixed up, though, and

Cherubino ends up falling into the garden where he's caught by the

Gardner (and Susanna's uncle) Antonio (bass-baritone Simon Dyer).

Susanna promises the Count a tryst, and things get far too complex to

enumerate here. Also involved are Antonio's daughter Barbarina

(soprano Sara Womble) with her aria that is inexplicably the sole

solo written in a minor key; a music teacher, Basilio (tenor Matthew

DiBattista); a judge, Don Curzio (tenor Brad Raymond); and two

bridesmaids (mezzo-sopranos Felicia Gavilanes and Emma Sorenson). In

the end, loose ends are tied up and the honeymoon car arrives.

|

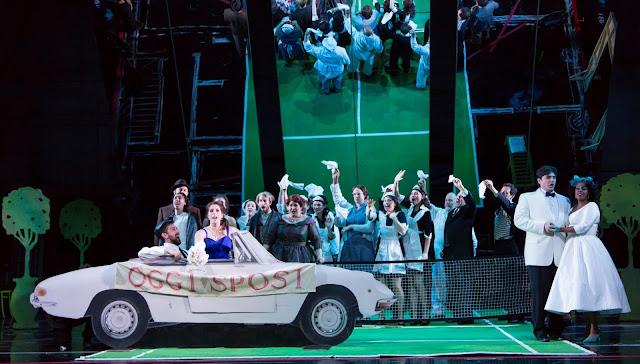

| The Cast at the Finale of "Marriage of Figaro" (photo: T. Charles Erickson) |

The performance was meticulously Conducted by David

Angus, with controversial Stage Direction by Rosetta Cucchi, unusual

Set Design by John Conklin, lovely Costume Design by Gail Astrid

Buckley and apt Lighting Design by D. M. Wood. The technical

elements were all one would expect from this company, especially the

rather unorthodox placement of a huge slanted mirror and chalked

floor spaces that Cucchi describes in the program notes as reflecting

two films, the 1954 Sabrina and the 2003 Dogville (in

which the chalked areas were equally strange and diverting in a bad

way). The on-stage presence of supernumeraries who were almost

constantly called upon for set changes, prop supplying and

complicated stagehand coordination helped keep the multiple plots in

play, but ended up adding to the distracting goings-on that were

usually irrelevant to the libretto, though accomplished with

precision and lightheartedness. Once again with this company,

though, the mounting of the work proved to be unnecessarily busy.

Just because this opera is so well-known and often performed doesn't

mean our minds would wander if left to the music of the moment.

That said, any production of this opera demands singers

who can act, and in that regard the composer would have been quite

pleased indeed. Hughes and Birsan made a believable couple who could

deliver musically and convey the lightness and poetry of the piece

with genuine musicality and sparkling presence. The same could be

said for Fons in full Keith Urban getup, as well as Pershall and

Heaston, representing the upper classes (perhaps of less impact in

the 1950's); Heaston in particular brought the house down with an

exquisite rendering of the Countess' aria. But then the entire cast

impressed with the level of apparent ease with such difficult music,

including the BLO Chorus under Michelle Alexander's direction. It

was a shame that the hall didn't perform as well as they did. Though

the makeover of the venue is visually pleasant, the acoustics are not

conducive to a crisp, responsive performance space; it was as though

one were revisiting one's dusty treasure trove of monaural LPs.

Thankfully, none of next season's offerings is scheduled for John

Hancock Hall.

Any opportunity to see and hear Mozart at his wittiest,

performed so brilliantly, is a chance that shouldn't be missed,

however. When that honeymoon vehicle finally arrives after three

hours of plot points, one needs no translation for the phrase with

which it is so amusingly bedecked: oggi sposi.

Repeat perfs: Sun.Apr.30 at 3:30pm, Weds.May 3 at 7pm, Friday May 5 at 7p & Sun.May 7 at 3:30p.

Repeat perfs: Sun.Apr.30 at 3:30pm, Weds.May 3 at 7pm, Friday May 5 at 7p & Sun.May 7 at 3:30p.